The Devon Buildings Group is concerned about building conservation issues of a general nature as well as specific case studies. Some have been around for a long time, some are relatively new. They all warrant discussion and constructive suggestions for more historic preservation oriented solutions.

Exeter Fire

Looking down into part of the Clarence from a cherry-picker in the High Street. Photograph by Todd Gray.

Looking down into part of the Clarence from a cherry-picker in the High Street. Photograph by Todd Gray.

Early on the morning of Friday 28th October 2016 a fire broke out in the Castle Fine Art Gallery in Cathedral Yard, Exeter. This developed into a major disaster extending over several days, the local fire service calling for help from Somerset, Dorset and Wiltshire. The progress of the fire is not fully-understood but it spread to the Well House, the pub adjacent to the art gallery. Burning debris fell on to the roof of the Clarence Hotel (occupying what were two separate historic buildings) to east and this caught fire, too . Sterling work by firefighters from all over the south west prevented its spread across St Martin’s Lane, at the east end of the block, although burning debris fell on Moll’s Coffee House and the gardens of houses at the north end of Cathedral Close – the block of buildings at right angles. The fire caused mayhem in Exeter. The old High Street was closed, as was the cathedral. Several businesses were closed down for several days, some are not re-opened at the time of writing. Thankfully there were no lives lost and no injuries.

The group of buildings most badly-affected by the fire. The Castle Fine Art Gallery to left; the double-gabled timber-framed 17th century Well House next door and the Royal Clarence Hotel at the right end. This consisted of two historic units, the 18th century purpose-built hotel and, at the right end, the former Exeter Bank, 18th century both with several phases of revision. JRL Thorp, photograph taken in 2015

The group of buildings most badly-affected by the fire. The Castle Fine Art Gallery to left; the double-gabled timber-framed 17th century Well House next door and the Royal Clarence Hotel at the right end. This consisted of two historic units, the 18th century purpose-built hotel and, at the right end, the former Exeter Bank, 18th century both with several phases of revision. JRL Thorp, photograph taken in 2015

Cathedral Green has been the heart of Exeter for nearly two millennia. On the edge of the Roman military fortress that was the origin of the City it was also the centre of the later Roman civilian settlement. Exeter was re-organised under the Anglo-Saxon reign of King Alfred in the late 9th century. It seems that it was then that building plots were established south from the High Street to the present frontage of Cathedral Yard on the north side of what is now Cathedral Close. Documents from the high medieval period – that is to say, from c.1100-1450 – show a significant and very interesting arrangement whereby the tenements on the north side of Cathedral Close indicate alternate ownership of what were the late Saxon tenements between the Vicars Choral and the Dean and Chapter.

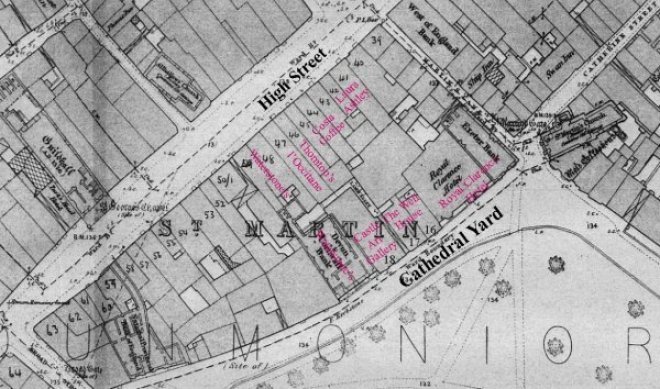

1876 OS 1:500 plan, annotated by Stuart Blaylock to show the current occupiers of the properties

1876 OS 1:500 plan, annotated by Stuart Blaylock to show the current occupiers of the properties

The block of buildings that stand (or stood, since the fire) on these ancient plots between Cathedral Green and the High Street have seen multiple phases of redevelopment over the centuries. On the Cathedral Green side they present (with some dull exceptions) distinctive elevations of mixed dates and styles, making up a worthy setting for the north side of the cathedral. Given the blitz damage to the City they include the amazing survival of a number of historic merchants’ houses including a run of nine houses along the High Street which are of serious national importance as they illustrate the development of urban housing from the late medieval period into the early modern. They include one medieval hall-house which was originally heated by an open hearth fire, and a number of later houses, sometimes built in pairs, illustrating the development of floored merchants’ houses from the early 16th to the early 18th century. Thanks to the presence of Todd Gray, on site during the fire, and the responsiveness of the fire service to information from him and John Allan about the importance of adjacent buildings, the losses have been less dreadful than they might have been. One example only of what has survived are the rooms spectacularly decorated with probably 17th century paintings on the upper floor of the 16th century Laura Ashley building .

What we know to have been lost is the interior of the Castle Fine Art Gallery. This was an architecturally eccentric 1870s building facing on to Cathedral Green, known to a few as having a fabulous first floor mirrored room and suite of spectacular flights of stairs. The building was scaffolded and in the course of upper floor conversion to flats. This building appears to have been entirely destroyed inside the shell. Next door to east is/was the Well House pub in a 17th century timber-framed merchant’s house or pair of merchants’ houses with a rendered front, the west block preserving original ribbon glazing to its bay windows. The east end block of the Well House had a flying freehold with the Clarence Hotel next door to east with hotel bedrooms at first floor level. The damage to the Well House is unclear at present, the roofs are badly-burnt but we do not know how far down the fire penetrated. The Clarence Hotel (Roman archaeology has previously been identified in an excavation of its kitchen) probably had a phase as a large clergy house. Its rebuilding in brick as a hotel in the 1760s incorporated 2 storeys of earlier, probably medieval Heavitree stone walling in the front facade. Thanks to the advice of Historic England, this walling has been retained, but the front above has been demolished and the interior is burnt out. The adjacent Exeter bank building, also 18th century in origin also appears to be burnt out. A collection of 27 important continental painted glass panels, often known as ‘Flemish roundels’, leaded into its ground floor windows, and likely to have been supplied to the hotel by the Drake family of cathedral glaziers and glass experts, have been damaged and some appear to have been destroyed.

Public meetings, prompted by Todd Gray and supported by the City Council, to explain the historic value of what has been lost and what has survived were held on 5th and 7th November in the Barnfield Theatre and were over-subscribed. Excellent papers were given by Todd, John Thorp, Richard Parker and John Allan. City Councillor Rachel Sutton, Andrew Pye, Principal Project Manager (Heritage) and representatives from the fire service and police were present to answer questions. Many people in Exeter, or who know the City, have described the fire as a personal bereavement. Perhaps the only Good Thing to come out of it is a reminder that familiar buildings are collectively highly valued as part of our sense of place: not just by those keen enough to be DBG members, but by a much larger and wider public who were very much in evidence at the public meetings. Many are aware of how much Exeter lost in the Blitz in 1942 and understand that the buildings round the cathedral are therefore an especially precious survival in addition to the historic importance of the site and individual buildings.

The public meetings had the character of a funeral where you discover just how interesting the deceased was and wish you had known sooner, as well as an occasion to find out more about some of the living. Most of what is known about the buildings, lost and surviving, derives from the work accumulated over decades of the Exeter Archaeological Field Unit and its successor organization, Exeter Archaeology. This knowledge has been supplemented by research and investigation carried out by building enthusiasts, e.g. Darren Marsh’s work on the documentary history of the Clarence Hotel and David Cook’s publication on the collection of stained glass. This has been a painfully sharp reminder of how important publications are and how precious the archives of Exeter Archaeology are, not only for information that could and should guide further archaeological work, but also what can and must be saved during restoration and, in the case of the Clarence Hotel, standing as a record of a largely lost historic building. It is difficult not to think that the closure in 2011 of Exeter Archaeology, supported by ECC from 1971 and a pioneer in applying archaeological methods to the recording of standing buildings, was a case of ECC counting costs but omitting to consider real value.

The demolition of the upper parts of the front facade of the Clarence on November 2nd. The brick front wall snapped off above the Heavitree stone construction. Photograph by Todd Gray.

The demolition of the upper parts of the front facade of the Clarence on November 2nd. The brick front wall snapped off above the Heavitree stone construction. Photograph by Todd Gray.

To date there is no information about how the fire began (there is a police investigation) how much more demolition might be unavoidable, how the Clarence might be rebuilt, what can be retrieved of the Well House and exactly how much damage there has been to adjacent buildings. There is obviously an archaeological opportunity to develop the records that have already been made of some of the buildings and better understand ‘St Martin’s Island’, as the block of historic buildings on these ancient plots has been dubbed since the fire. It is also profoundly hoped by the DBG that this catastrophe will prompt the completion of work to fully-record the important High Street buildings (some of which are not known in detail). It would be some consolation if the fire prompted the funding for accessible-to-all publications about the buildings around the cathedral.

Todd Gray is to be heartily thanked for his energetic presence on site during the fire, for dealing with the press and for responding to the widely-shared sense of loss in organising the public meetings.

Jo Cox and John Thorp

Other Topical Issues:

VAT on works to historic buildings: For a number of years organisations concerned about historic building conservation and restoration have criticised the inequity of the VAT regulations which mean that VAT has to be paid on repairs to listed residential buildings, but strangely not on works to alter or extend them. As the former would conserve their character and the latter would probably not, this is clearly illogical, but the Treasury has resisted any change to date. Given that owning a listed building can be a financial imposition, zero-rating repairs would appear to be a minimal concession.

Satellite dishes: prompted by the change-over from analogue to digital television signals an extraordinary number of satellite dishes are appearing on houses. Like mushrooms they seem to pop up, usually in prominent places on chimneys and gables, often in full sight from the road. We can only hope that technology will soon provide a less unsightly option.

School refurbishment: CABE, the Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment, has recently published “New from old: transforming secondary schools through refurbishment”. This points out what conservation organisations have long been promoting, namely that it is often much better to restore than replace. To find out more, go to http://tinurl.com/c2rsje. Richard Parker’s article “School Buildings in Exeter 1800-1939” in the DBG’s Newsletter, number 22, dated October 2004 is but one manifestation of our concern about such buildings across the county.

The matter of restoring or converting existing school buildings is very much of the moment, with roughly £20 billion expenditure on school buildings from various sources anticipated in the next few years. English Heritage has posted a fascinating paper on its website (www.english-heritage.org.uk/server/show/nav.21443) and as recently as 10 February included a second paper on its Newsletter (see newsletter@english-heritage.org.uk) A most comprehensive site on the subject is www.helm.org.uk/server/show/nav.19652. We recommend them.

Cobbling: concerns regarding how historic cobbles are being torn up and replaced with mass produced manmade flags continue. The DBG Newsletter, No 31, Summer 2013, included an article attempting to show the wide range of patterns and uses of historic cobbling and stressing how much character and charm they add to villages and churchyards. While we sympathise with and support the needs of less able visitors to historic sites, especially churches, there are simple alternative means to make paths smoother and less worrying. Resetting the stones (ie proper maintenance), providing an alternative route or covering the cobbles with a removable protective covering have all been successfully carried out. There is no need to destroy the existing cobble surfaces, they can meet current needs and should co-exist with the installation of a new surface. The money spent on replacement would be much better used to maintain the existing.

Local Development Orders, Strategic Stone Survey and Disused Quarries: An article written by Mark Smulian in the Planning Resource Daily Bulletin of Planning Daily dated September 3rd 2010 is of particular interest to the DBG. It is complex and worth consulting in its entirety at www.planningresource.co.uk/bulletins/Planning-Resource-Daily-Bulletin/InDepth/1025384/Called-order/?DCMP=EMC-DailyBulletin

It concerns Local Development Orders (“LDOs”) which “are intended to allow councils to grant permitted development rights beyond those available nationally in a defined area. They were originally intended as a way of managing small-scale change and cutting planning workloads for minor schemes.”

Despite a lengthy process of consultation and the requirement for ministerial authorisation, there is concern “that changes to buildings might be allowed without planning permission runs the risk of igniting uproar from conservation and environmental groups…”

Generally take-up of LDOs has been slow and patchy. Devon County Council’s proposed LDO is unusual in not covering predefined areas but to encourage the extraction of local stone needed “to refurbish buildings with appropriate materials. There is no shortage of materials but most of the small quarries that would once have extracted them have long been shut down.”

Also relevant is the Strategic Stone Survey, established by English Heritage and working with the British Geological Survey “to catalogue the rich variety of English building stone, including their historic sources, their patterns of use and culturally significant buildings and villages in which they have been used”. First edition OS maps, existing building records and the work of local and regional specialist groups will be fed in to the data base. For more information see the Vernacular Architecture Group, Newsletter number 59, June 2010, pp 22-24.

This issue is timely in part because of the DBG’s fascinating 2009 Summer Conference at the Beer Quarry ( see also DBG Newsletter Number 27) and in part because of the concerns raised at the 2010 AGM in Sandford regarding disused quarries being uses as waste disposal sites. Conveniently, the responsibility for both Minerals and Waste fall within the same part of the Devon County Council’s environment department, so joined up thinking should not be a problem.

Please let us know about any issues which are of particular concern to you, either in your own community or of a more general nature.